Introduction

Picture a lazy Sunday in a Punjabi household: the whole family gathers as the kitchen fills with the mouthwatering aroma of ghee. On the tawa (griddle), Lachha Parathas sizzle and puff up, promising a hearty treat. Lachha Paratha is a beloved North Indian flatbread (often dubbed a Punjabi bread) known for its crisp, flaky layers. In many Punjabi families, weekend meals or festive thalis (traditional feast platters) feel incomplete without a stack of these golden, multi-layered parathas at the center. The name “lachha” literally means layers (or rings), and indeed each paratha reveals concentric rings of dough when cooked, a testament to the unique folding technique that creates its signature flaky texture. It’s an all-time favorite comfort food, lovingly served during special breakfasts, family get-togethers, and celebratory dinners alike. One bite into a warm lachha paratha – with those ghee-brushed layers melting in your mouth – and you’ll understand why this bread holds a special place in Punjabi cuisine.

Lachha Parathas are traditionally cooked on a hot griddle with ghee until they turn flaky and crisp, revealing their beautiful ring-like layers. These buttery flatbreads are best enjoyed fresh off the tawa with a dollop of ghee or butter melting on top for extra indulgence. Serve them immediately while hot to fully appreciate the tender layers and golden-brown crunch of each paratha.

Ingredients

To make Lachha Paratha at home, you’ll need just a few pantry staples:

Whole Wheat Flour (Atta) – 2 cups (the base for an authentic Punjabi lachha paratha)

Salt – 1 teaspoon (to taste)

Ghee or Oil – ~4 tablespoons (use ghee for genuine flavor and flakiness; some for the dough and more for cooking)

Water – ~¾ to 1 cup (for kneading a soft dough)

Optional: A tablespoon of all-purpose flour (maida) can be mixed into the wheat flour for extra softness, and a pinch of ajwain (carom seeds) can be added for aroma (this is optional, but some traditional recipes include it for a subtle flavor). You can also keep a little extra dry flour handy for dusting and a bit more ghee for layering and frying.

Step-by-Step Instructions

Follow these steps to prepare flaky, layered Lachha Parathas from scratch:

1. Make the Dough: In a mixing bowl, combine the whole wheat flour and salt. Drizzle 1 tablespoon of melted ghee (or oil) into the flour. Rub the ghee into the flour with your fingers until it’s well incorporated (this step makes the parathas soft and flavorful). Gradually add water, a little at a time, and mix until a shaggy dough forms. Knead the dough for about 5–8 minutes to make it smooth and pliable. The dough should be soft but not sticky. (Tip: A well-kneaded dough is key – kneading develops the gluten, making it easier to roll out thin layers.) Gather the dough into a ball, smear a tiny bit of ghee on its surface, and cover it with a damp cloth. Let it rest for 20–30 minutes. Resting relaxes the dough, making it easier to roll out later.

2. Divide and Shape Balls: After resting, give the dough a quick second knead. Divide it into equal portions – you should get about 6–8 medium dough balls from this quantity (for larger parathas, make 6). Roll each portion between your palms to make smooth balls. Keep the dough balls covered to prevent drying out.

3. Roll Out the Disc: Take one dough ball at a time. Dust your work surface and rolling pin lightly with dry flour. Flatten the ball and roll it out into a thin disc, roughly 8–10 inches in diameter. Don’t worry if it’s not a perfect circle – the key is to get it thin (around 1 mm thickness). You should almost be able to see a bit of light through the rolled dough.

4. Apply Ghee and Flour (Layering): Spread a generous teaspoon of ghee all over the surface of the rolled dough – use a brush or your fingers to coat it evenly. Next, sprinkle a pinch of dry flour on top of the greased dough. (This little flour trick helps create distinct flaky layers by preventing the folded dough from fully sticking together.) Now comes the classic lachha folding: starting from one end of the circle, fold the dough into pleats as if you’re making a paper fan or a sari pleat. Make ½-inch pleats all the way to the other end – the more pleats, the more layers your paratha will have. You’ll end up with a long strip of pleated dough.

5. Form the Layers: Gently stretch the pleated strip a bit longer. Then roll it up tightly into a coil, like a spiral or “snail shell,” tucking the end underneath. You will now have a coiled dough round that already shows a spiral pattern of layers. Lightly press it with your palm to flatten it slightly. Prepare all dough balls this way. If you have time, let the coiled dough rounds rest for 5–10 minutes (this helps the layers fuse and prevents shrinking when rolling out).

6. Roll Out the Paratha: Take one coiled dough round, dust it lightly with flour on both sides, and gently roll it out again. Do not press too hard while rolling – use a light hand to preserve those layers. Roll it into a flat circle about 6–7 inches in diameter. It will be thicker than a regular roti, and you should see the spiral layers within the rolled dough. If needed, dust off excess flour. Repeat this process for all the coiled dough portions.

7. Cook on Tawa: Heat a heavy tawa or flat skillet over medium heat. When hot, carefully place the rolled paratha onto the tawa. Cook for about 30 seconds to 1 minute until the bottom side gets light brown spots and the dough changes color. Flip the paratha. Now drizzle ~½ teaspoon of ghee around the edges and on top. Cook this side until it sizzles and develops golden-brown patches. Flip again and apply ghee on the other side as well. Gently press the paratha’s surface and edges with a spatula, moving it in circles – this helps it puff up in places and ensures even cooking. Cook until both sides are golden-brown and crisp, with distinct flaky layers visible on the surface. Each paratha may take 2–3 minutes to cook. Adjust the flame between low-medium as needed: too high heat can brown it too fast leaving inner layers undercooked, while moderate heat allows it to crisp up nicely. Once done, remove from heat and optional: brush a bit more butter or ghee on top. Serve hot. Continue frying the remaining parathas the same way.

Tips for Perfect Flaky Layers

Creating those bakery-style flaky layers in Lachha Paratha can be tricky, but these tips will help you get it just right:

Use Ghee Generously: Ghee is the magic ingredient that yields soft yet crispy layers. Knead a bit of ghee into the dough and definitely use ghee (not just oil) for layering and frying – it imparts a rich aroma and keeps the paratha tender and flaky. Parathas made with ghee will be much more flavorful and crisp than those made with oil.

Sprinkle Flour Between Layers: When you brush the rolled dough with ghee, also sprinkle a pinch of dry flour over it before folding. This clever trick helps to separate the layers. As one recipe notes, even about half a teaspoon of flour over the greased dough can prevent the layers from sticking completely, yielding ultra-flaky results.

Pleat Tightly & Roll Gently: Make as many pleats as you can – thin, accordion-like folds ensure numerous layers. Roll the pleated strip into a tight coil to build up the layers. Later, when rolling out the layered dough, be gentle. Do not apply heavy pressure with the rolling pin; otherwise you’ll squish the layers together. Roll lightly and only to the size needed. A thicker paratha (within reason) will have more visible flaky tiers, whereas rolling too thin can merge the layers.

Moderate Heat is Key: Cook the paratha on a moderately hot tawa. Too low heat will dry it out and make it hard rather than flaky. Too high heat will char the outside quickly while inner dough may remain raw. A steady medium flame allows the paratha to crisp up beautifully and cook through. You want a golden-brown color on each side. Add ghee during frying to help it turn a lovely golden and to fry the layers to a slight crisp.

Toss or Crush to Separate Layers: A pro tip for extra-flaky texture – once a paratha is cooked, gently crush it or clap it between your hands (careful, it’s hot!) to separate the layers slightly. You’ll see the lachha layers “bloom” out. This also keeps it from becoming flat or soggy. Restaurants often lightly smack the parathas to highlight the flaky layers.

Serve Immediately: Lachha Parathas taste best when they’re fresh off the pan. The longer they sit, the more they tend to toughen or lose flakiness. Have everything else ready to eat, so you can enjoy the parathas piping hot. If you must reheat, use a tawa on low heat rather than a microwave (which can make them chewy).

By following these tips – using plenty of ghee, proper folding technique, and the right heat – you’ll get parathas with gorgeous, bakery-like layers that are flaky on the outside and soft on the inside.

Serving Suggestions

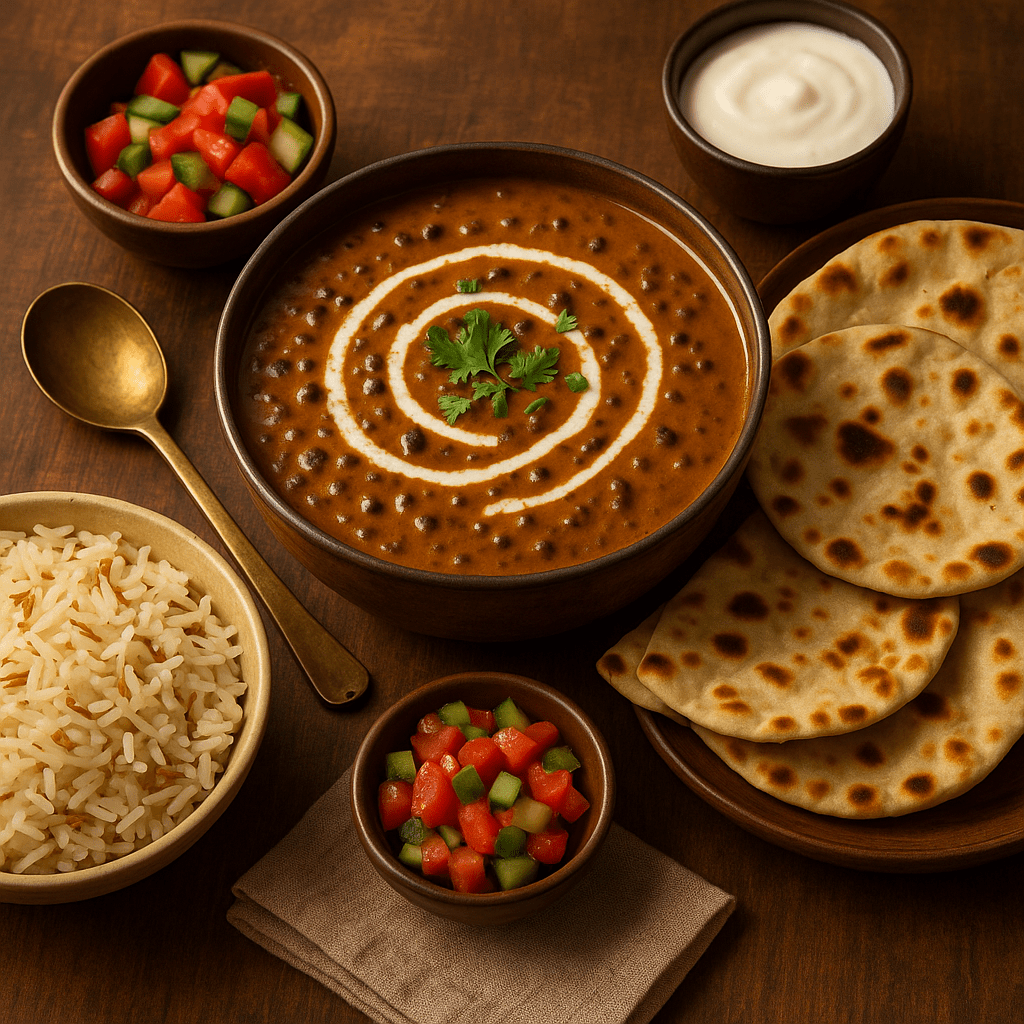

Lachha Paratha is a versatile bread that pairs well with many North Indian dishes. Here are some classic pairings to complete your meal:

Dal Makhani: A rich, slow-simmered lentil dal (usually made with whole black urad dal and kidney beans) cooked with butter and cream. The creamy, smoky flavor of Dal Makhani is a match made in heaven with flaky lachha parathas – perfect for scooping and savoring.

Paneer Butter Masala: This smooth tomato-based curry with soft cottage cheese (paneer) chunks is mildly spiced and slightly sweet. Scooping up the luscious Paneer Butter Masala gravy with a crisp lachha paratha is pure bliss. The buttery paratha complements the buttery gravy beautifully.

Punjabi Chole (Chickpea Curry): Spicy, tangy chickpea masala (chana masala or Pindi chole) makes for a hearty combo. The layers of the paratha soak up the flavorful gravy. Add some sliced onions and a squeeze of lemon on the side, and you have a rustic Punjabi favorite.

Pickle and Curd: For a simple accompaniment, serve lachha parathas with a side of achar (Indian pickle – such as mango or chili pickle) and plain dahi (yogurt) or raita. The tang of the pickle and the coolness of yogurt balance the paratha’s richness. Many enjoy a hot paratha just with a dollop of homemade white butter, a bit of mango pickle, and a spoon of creamy yogurt – comfort food at its best.

Paneer Bhurji or Curry: Aside from Paneer Butter Masala, any paneer dish works well. Paneer bhurji (spiced scrambled paneer) or Palak Paneer (spinach and paneer curry) are great choices to serve alongside. The paratha’s mild taste lets the curry shine, and its texture stands up to thick gravies.

Breakfast Combo: You can even enjoy lachha parathas for breakfast by pairing them with masala chai (spiced milk tea) and perhaps an omelette or fried eggs. In Punjab, a common breakfast is parathas with lassi (a sweet or salted yogurt drink) – filling and satisfying.

Whether you serve these parathas with a deluxe curry like Dal Makhani or something simple like spiced pickle and curd, be sure to relish them hot. The flaky layers, when warm, are wonderful for mopping up any sauce or flavorful curry. And don’t forget to add that pat of butter or ghee on top of the parathas just before serving – it takes the indulgence to the next level!