The cold months in Odisha bring a bounty of vegetables. Local haats overflow with cauliflower heads, pumpkins, raw bananas and tubers, as one blogger marvels at *“the most glorious winter produce on display. Greens dominated the scene with generous pools of white. Reds, pinks and purples stood out conspicuously…”*. Every Odia kitchen begins to crave comfort foods. Among them, Dalma – a spiced lentil-and-vegetable stew – is king. It’s a dish steeped in tradition and warmth: *“a traditional dish from Odisha…known for its wholesome combination of lentils and vegetables”*. Before tucking in, families often whisper the old prayer “Anna Brahma… Vasundhara Lakshmi” – acknowledging food as divine. In fact, Dalma is so revered that Puri’s Jagannath temple serves it daily as Mahaprasad. On chilly nights, a pot of this ghee-scented stew is as welcome as a warm blanket, filling the home with nostalgia and devotion.

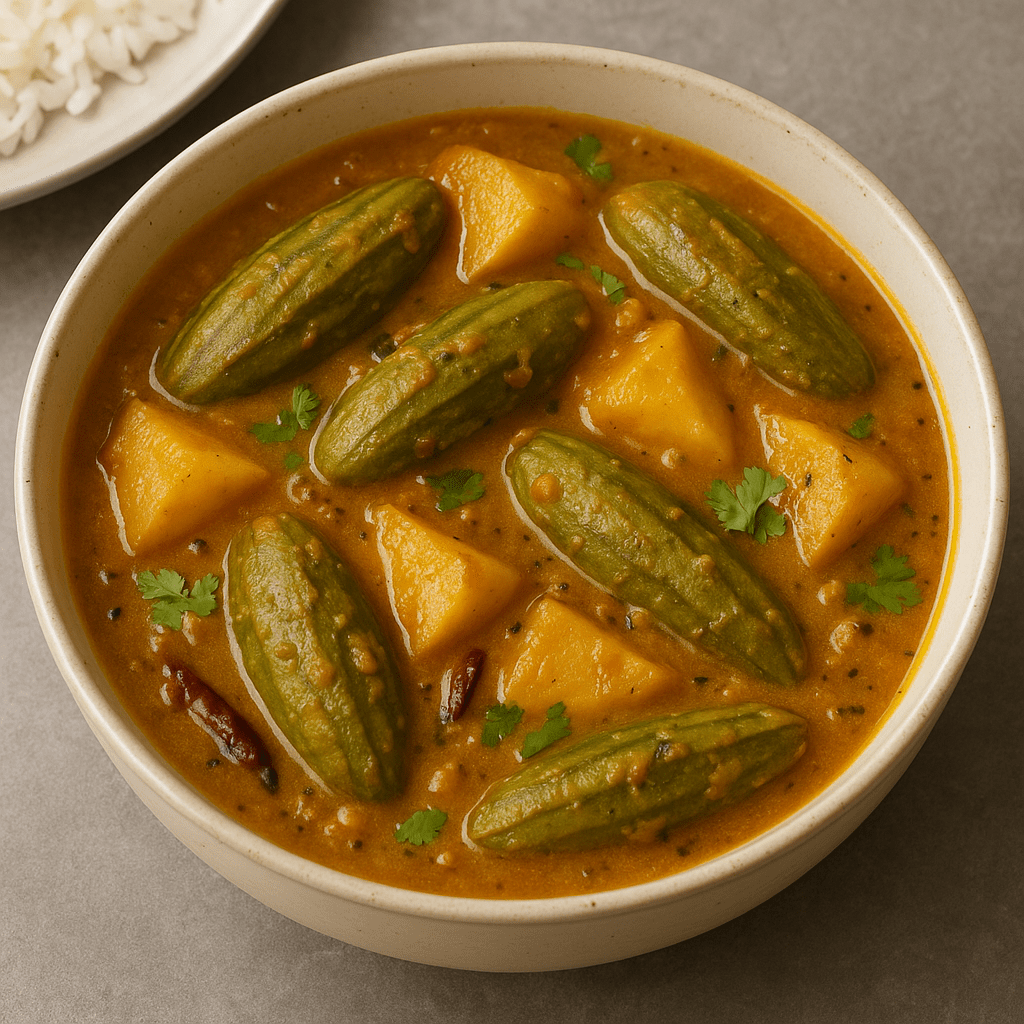

In this cozy bowl of Winter Dalma, steamed rice is ready to receive the curry. Our recipe starts with arhar dal (toor dal) simmered soft with seasonal veggies. For example, one recipe suggests adding chopped pumpkin, potato, tomato and raw banana – you can also stir in cauliflower florets, green beans, carrots or drumsticks as available. After the dal is cooked, we make a fragrant tempering: heat ghee (or mustard oil) and crackle a teaspoon of each Panch Phoran seed (fenugreek, nigella, cumin, mustard, fennel) with dried red chilies. At home we always add minced garlic cloves at this stage for extra warmth (temple cooks omit garlic for purity). The sizzling spices go into the dal-pot, giving the Dalma its signature aroma. This humble ghee‑rich curry is deeply rooted in Odia life – it even figures on the Lord Jagannath Abadha (kitchen offerings) every day, a true symbol of Odisha’s rustic, devotional cuisine.

Ingredients

1 cup toor dal (arhar dal) – washed (you may soak it 20–30 minutes to shorten cooking).

Water – about 3 cups for cooking dal (plus additional for vegetables).

Seasonal vegetables, roughly chopped: e.g. 1 cup cauliflower florets, ½ cup diced pumpkin, 1 raw banana (sliced), 1 medium potato (cubed), ½ cup green beans (cut into 2″ pieces). (Feel free to add carrot, yam, drumsticks or taro as available.)

1–2 tomatoes, chopped (optional – adds tang and color).

1 teaspoon turmeric and salt to taste.

3 tablespoons ghee (or mustard oil).

Garlic – 2–3 cloves, minced (omit for satvik version).

Panch Phoran mix – ½ teaspoon each of mustard seeds, cumin seeds, fenugreek seeds, nigella seeds (kalonji), and fennel seeds; or use 1 tsp each cumin and mustard seeds (jeera‑rai) if Panch Phoran isn’t on hand.

2 dried red chilies.

Pinch of asafoetida (hing) (optional, for aroma).

Fresh grated coconut (for temple-style variation).

Fresh cilantro (coriander), chopped (for garnish).

Method

1. Pressure-cook the dal: Drain the soaked dal. In a pressure cooker, combine the dal with 3 cups water, turmeric and a pinch of salt. Cook for 3–4 whistles (or until very soft). Allow the pressure to release naturally, then mash the dal lightly with the back of a spoon.

2. Cook the vegetables: While the dal cooks, heat 1 tbsp ghee in a pan and briefly sauté the firmer veggies. Add the pumpkin cubes, potato, raw banana, and any yam or root veggies; toss with a little salt and cook for 2–3 minutes. (This step ensures very hard veggies start to soften.) Transfer these into the dal along with another 1–2 cups of hot water. Add the remaining vegetables (beans, cauliflower, tomatoes) on top. Pressure-cook again for 1–2 whistles, or simmer in a covered pot until all veggies are just tender. (By adding delicate veggies later, you keep them from turning to mush.)

3. Prepare the tempering: In a small pan, warm the remaining 2 tbsp ghee. Add the Panch Phoran seeds (or cumin and mustard seeds) and let them sputter. Slip in the dried chilies and minced garlic, and a pinch of hing if using. Fry gently until the garlic is golden and everything smells fragrant.

4. Combine and simmer: Pour the hot tempering into the dal-vegetable stew. Stir well. Check seasoning and salt. Let the curry simmer on low for 3–5 minutes so the flavors marry. If using coconut (see variation below), stir it in now. The Dalma should be stew-like – add a little extra hot water if it seems too thick. (If it’s too thin, simply simmer uncovered a few minutes to reduce it.)

5. Finish with aromatics: Turn off the heat. Adjust salt and consistency. Swirl in a teaspoon of ghee and garnish with chopped cilantro (and a sprinkle of grated coconut for extra richness, if you like).

Temple-Style Satvik Dalma (No Onion/Garlic)

For a pure satvik or temple version, skip garlic entirely. The Dalma is cooked slowly in an earthen pot or heavy-bottomed pan. In place of the usual tempering, you simply stir in fresh grated coconut at the end along with the ghee. Pinch of Masala notes that temple Dalma is “slow-cooked… No onion or garlic — satvik simplicity is key” and that one should “add freshly grated coconut to dalma… for richness”. The result is a light, creamy curry laced with coconut’s sweetness – solemn and sacred, perfect for puja offerings or fast days.

Tips for Perfect Dalma

Adjust the consistency: Dalma thickens as it cools. If it’s too watery, simmer a little longer uncovered to reduce it; if it’s too stiff, add hot water when reheating. A well-balanced Dalma should coat the vegetables but still be slightly runny. Simmering uncovered will thicken it up, while a splash of boiling water thins it out.

Stagger the veggies: Add hardy vegetables (yam, pumpkin, potato) first, then tender ones (beans, tomatoes, greens) later. This way nothing overcooks – “vegetables should be tender but not mushy”. (For example, add spinach or mustard greens right at the end off the heat, so they wilt but keep color.)

Balance the flavors: Taste before the final simmer. You can brighten it with a squeeze of lemon or a dash of jaggery if you like, but traditional Dalma needs little else besides salt and turmeric. Finish with a flourish of ghee or grated coconut for luxury.

Reheating: Leftovers get thicker in the fridge. Warm Dalma slowly on the stove with a splash of water. Stir occasionally; the dal will loosen up and the spices mellow. Stored in an airtight container, Dalma keeps well for 2–3 days.

Authentic aroma: For the most “temple-like” aroma, cook on a gentle flame and, if possible, in an earthen or cast-iron pot. Use pure cow’s ghee (it’s considered an offering in itself) and never rush the cooking.

Serving Suggestions: The Odia Thali

Winter Dalma is best enjoyed with steaming rice (or pakhala, fermented rice) to soak up its juices. Round out the meal with crunchy, tangy sides. In Odisha, it’s common to serve rice and Dalma with bādi chura (a mix of crushed sun-dried lentil dumplings mixed with onions and chilies) and sāga bhajā (stir-fried leafy greens). These provide a textural contrast – the crisp, spicy badi chura and sautéed greens balance the creamy Dalma. A simple aloo chakata (spiced mashed potatoes) and a zesty pickle on the side are traditional favorites, too. Together, they recreate the festive, comforting vibe of an Odia winter feast: hearty, wholesome, and served with heartfelt devotion.