There’s a chill in the air and the fields are a sea of yellow mustard blossoms. In Punjabi households, this can only mean one thing: sarson ka saag season is here. Growing up, I remember sitting in my grandmother’s kitchen on a sunny winter afternoon, watching her patiently cook sarson ka saag in a heavy brass pot over the chulha (wood-fired stove). The aroma of mustard greens, spinach, and bathua simmering slowly with ginger and garlic would fill the house, building our anticipation. She would use a wooden madhani (hand churner) to gently mash the greens – an old-fashioned technique that gave the saag its rustic, slightly coarse texture. No blenders back then, just slow cooking and a lot of love. It’s often said that authentic sarson ka saag is a labor of love, requiring time and patience to get the flavors just right. And truly, after hours of bubbling away, what emerged was a pot of gold (or rather, emerald green) – creamy, hearty saag ready to comfort everyone on a cold evening.

A Taste of Tradition: Sarson ka saag isn’t just food; it’s a tradition and an emotion. This dish of spiced, pureed mustard greens is the pride of Punjabi winters, commonly enjoyed from late November through February when mustard leaves are freshest. Winter is the season when mustard (sarson) and bathua grow abundantly in North India, which is why this saag became a quintessential cold-weather dish in Punjab. Families often mix mustard greens with other seasonal greens like spinach and bathua (wild goosefoot) to balance the mustard’s spicy bitterness. The result is an earthy, mildly bitter greens curry that’s bursting with flavor and nutrients (so much so that an extra dollop of butter on top is completely justified!). Traditionally, the saag was slow-cooked for hours in a brass patila (pot) or clay handi on a low fire, which old-timers swear deepens the flavor. I’ve heard of folks using a century-old brass pot passed down through generations to make this dish, stirring it periodically with that wooden churner until the greens reach silky perfection. It’s no wonder that come winter, Punjabis look forward to cozy meals of sarson ka saag and makki di roti (maize flour flatbread) to warm the soul.

Nostalgia in Every Bite: The very serving of sarson ka saag can evoke nostalgia. Picture a brass thali (plate) or katori brimming with luscious green saag, a pat of homemade white butter (makkhan) melting slowly on top. Beside it rests a stack of Makki di Roti swathed in ghee, and on the side, a few sticks of gur (jaggery) and slices of crisp white radish. In my family, we’d even finish the meal with a bite of jaggery – the sweetness perfectly balances the slight bitterness of the greens and signifies the end of a hearty Punjabi feast. As a food writer once described, a tiny bowl of glistening homemade butter slathered on warm makki rotis and dipped into the saag can entice even the pickiest eater. Indeed, sarson ka saag with makki di roti isn’t just a meal – it’s winter comfort on a plate, a symbol of Punjabi hospitality, and a reminder of simpler times when food was slow-cooked with love.

Ingredients

To make traditional Sarson ka Saag, you will need the following:

Mustard greens (Sarson) – ~1 bunch (500 g), stems trimmed. These peppery mustard leaves give the saag its signature pungent flavor and are the star of the dish.

Spinach (Palak) – ~1/2 bunch (250 g). Adds mild sweetness and balances the mustard’s bitterness.

Bathua leaves – ~1/2 bunch (150–250 g), if available. Bathua (wild goosefoot) is a traditional addition that gives authentic flavor and helps mellow the mustard greens. If you can’t find bathua, you can use a little extra spinach or even fenugreek leaves.

Ginger & Garlic – 2 inches ginger and 6–8 cloves of garlic, finely chopped or grated. These aromatics infuse warmth and depth into the saag.

Green Chilies – 2–3 (or to taste), slit or chopped. For that gentle heat. You can adjust or skip for a milder saag.

Maize flour (Makki ka Atta) – 2–3 tablespoons. This fine cornmeal is crucial – it thickens the saag and also tones down the bitterness of the mustard.

Onion – 1 medium, finely chopped. Used in the tempering (tadka) for a subtle sweetness.

Ghee or Butter – 3–4 tablespoons. Used for cooking and for the finishing tadka. Ghee adds a lovely richness and authentic flavor.

Spices & Seasonings: Cumin seeds (1 tsp), salt (to taste), red chili powder (1/2 tsp, adjust to taste), turmeric powder (1/4 tsp, optional for color), garam masala (1/2 tsp, optional). Punjabi recipes are actually quite restrained with spices for this dish – the emphasis is on the greens. Just a hint of spices enhances the saag without overpowering the natural flavors.

Note: The ratio of greens can be adjusted. A common traditional proportion is 2 parts mustard : 1 part spinach : 1 part bathua. So if you have 500 g mustard, use ~250 g each of spinach and bathua. Don’t worry if you can’t be exact – the beauty of this recipe is that you can tweak the mix of greens based on availability. Fenugreek leaves (methi) or radish greens can also be thrown in for a twist, but mustard should remain the dominant portion.

Instructions (Step-by-Step Recipe)

Follow these steps to prepare Sarson ka Saag the traditional way. This recipe is meant to be leisurely, so put on some music or maybe call your mom for a chat while the greens cook – we’re channeling slow cooking, Punjabi-style!

1. Prep the Greens: Thoroughly wash all the leafy greens (mustard, spinach, bathua) to remove any grit – this may take 3-4 rinses since mustard leaves can be quite muddy. Chop the leaves roughly and discard any thick stems. (Tip: Cleaning the greens well is the most labor-intensive part, but it’s essential for a grit-free saag.) You should have a big mound of mixed greens; don’t worry, it will cook down significantly.

2. Cook until Tender: Place the cleaned, chopped greens in a large deep pot. Add about 2–3 cups of water (just enough to cover the greens). Toss in 2-3 chopped garlic cloves, half the ginger, and 1-2 green chilies. Also add 1/2 tsp salt to help the greens cook. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a low simmer and cover, allowing the greens to cook until completely soft. This can take around 30-40 minutes on the stovetop, stirring occasionally. (Traditionally, the greens were simmered for even longer, sometimes over an hour on low heat, to achieve that melt-in-mouth texture and to let the flavors deepen – truly slow cooking!). You’ll know it’s ready when the mustard leaves are tender and the kitchen smells like verdant, earthy goodness. (Quick alternative: You can pressure cook the greens with a little water for 1-2 whistles to save time, but purists prefer the slow simmer method for maximum flavor.)*

3. Mash/Blend the Greens: Once the greens are cooked, let them cool slightly. Then mash them into a coarse purée. Traditional method: Use a wooden madhani (hand churner) or a masher to churn the greens in the pot for several minutes. This manual mashing gives a wonderful rustic texture – you want the saag to be somewhat coarse, not a baby-food puree. Modern method: Alternatively, transfer the softened greens (with a bit of the cooking liquid) to a blender and pulse a few times until you get a medium-coarse paste. Do this in batches if needed. (Be careful with hot liquids in a blender; allow cooling or use an immersion blender.) Do not over-blend – authentic sarson ka saag has some leafy texture to it, so it shouldn’t be completely smooth.

4. Simmer with Makki ka Atta: Return the mashed greens to the pot (if you removed them) and place it back on low heat. Stir in the maize flour (makki ka atta), sprinkling it evenly and mixing continuously to avoid lumps. The cornmeal will thicken the saag as it cooks. Add a splash of hot water or the reserved cooking liquid if the mixture looks too thick initially. Now let the saag simmer on low heat for another 15-20 minutes, stirring every few minutes so it doesn’t stick to the bottom. This slow cooking with the corn flour is important – it eliminates the raw taste of the cornmeal and really allows all the flavors to meld beautifully into a creamy, homogenous saag. You’ll see the color of the saag deepen and the texture become velvety. (At this stage, your patience will be rewarded – as the pot bubbles gently, the aroma is irresistible!)

5. Prepare the Tadka (Tempering): In a separate pan, heat 2-3 tbsp of ghee (or butter). Add 1 tsp of cumin seeds and let them sizzle for a few seconds until aromatic. Then add the chopped onions and sauté on medium heat until they turn golden-brown. Next, add the remaining chopped garlic and ginger. Sauté for another minute until the raw smell disappears. (Some families also add 1-2 chopped tomatoes at this point, cooking them down to add a slight tang, but the traditional recipe often skips tomatoes. Feel free to include one tomato, chopped, and cook until it’s soft and the oil separates, especially if you like a hint of tang in your saag.) Now sprinkle in the spices: a pinch of turmeric, red chili powder to taste (if you want extra heat or color), and 1/2 tsp garam masala (if using). Stir for a few seconds to bloom the spices in the ghee – be careful not to burn them.

6. Combine Tadka with Saag: Pour this hot, fragrant onion-garlic masala (tadka) into the simmering pot of saag. You’ll hear a satisfying sizzle as it all meets. Stir everything together so the tempered ghee and aromatics mix well with the greens. Let the combined saag cook for another 5-10 minutes on low heat, so the flavors marry. At this point, check for seasoning and add salt if needed. If the saag looks too thick, you can add a bit more water and simmer a few minutes; if it’s too thin, cook a little longer to evaporate excess liquid. The final consistency should be like a medium-thick porridge – not runny, but flowing and creamy.

7. Finishing Touch (Optional Tadka): For extra indulgence and aroma, you can do a quick final tempering. In a small tadka pan, heat 1 tbsp ghee. Add 1-2 sliced garlic cloves and 1 dried red chili (broken). Fry for just half a minute until the garlic turns lightly golden and the red chili infuses the ghee (don’t let them burn). Turn off the heat and sprinkle a pinch of red chili powder in the hot ghee – this will instantly release a wonderful color and aroma. Drizzle this infused ghee on top of the prepared sarson ka saag just before serving. This step is optional but highly recommended for that restaurant-quality presentation and an extra layer of flavor. You’ll see the red-spiced ghee shimmering on the green saag – mouthwatering!

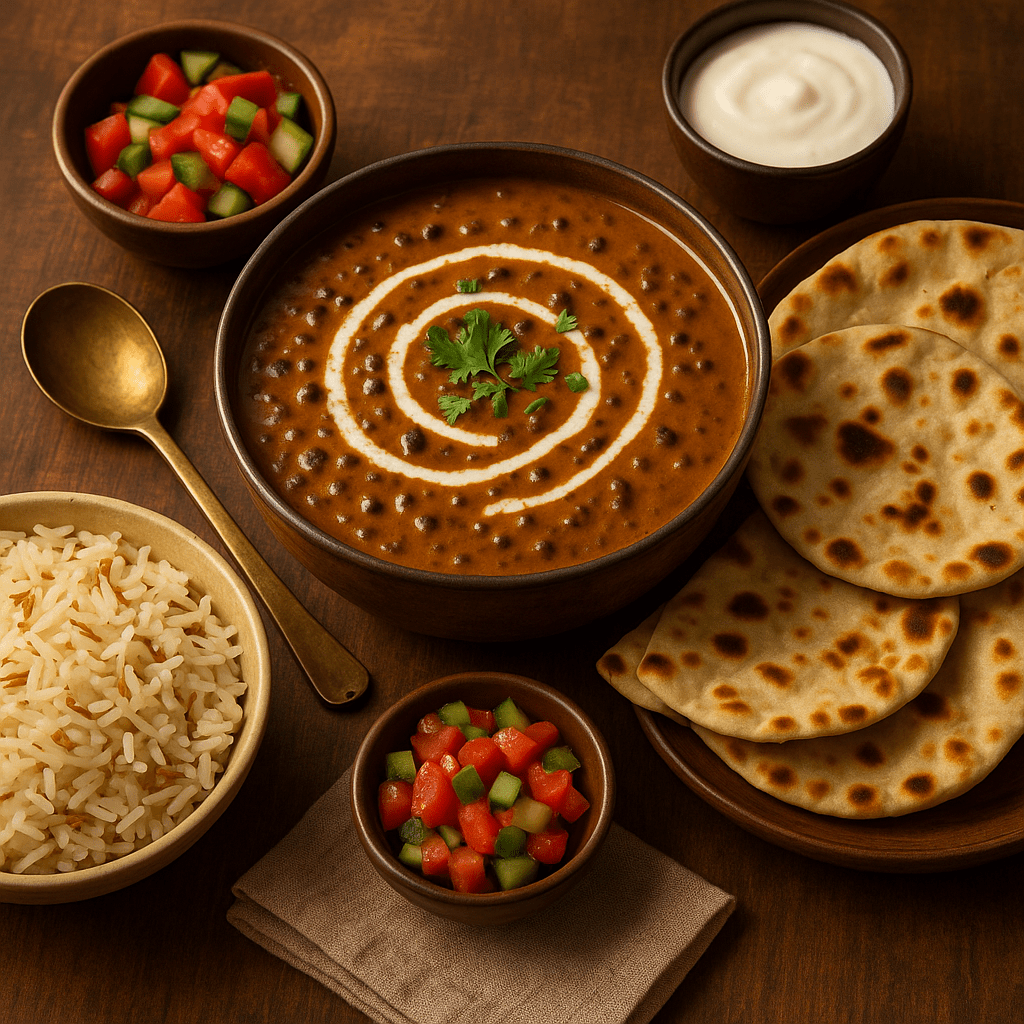

8. Serve: Sarson ka saag is best served hot, straight from the pot, with a generous dollop of makkhan (white butter or ghee) melting on top. The traditional accompaniment is Makki di Roti, the famous golden-yellow cornmeal flatbread, which you can make by kneading maize flour with warm water into a dough, patting it into flatbreads and cooking on a hot tawa (griddle). Serve the saag with makki rotis smeared with butter – this combination is soul-satisfying and authentic. Don’t forget to keep some sides like chopped onions, green chilies, and mooli (white radish) to munch on for freshness and crunch. And as many Punjabi households do, serve a little piece of jaggery (gur) on the side – a bite of jaggery after a spicy saag and roti mouthful is a divine sweet contrast that also helps cut any lingering bitterness. Now dig in and enjoy your hearty winter meal!

A traditional Punjabi spread of Sarson ka Saag with Makki di Roti on a brass thali, accompanied by white butter, radish, and even a bowl of boondi raita. The vibrant green saag is garnished with a drizzle of aromatic ghee tempered with garlic and red chili, and a dollop of homemade butter on top. A few slices of white radish (mooli), some green chili, and jaggery on the side complete this homestyle winter feast.

Conclusion

In the end, Sarson ka Saag is more than just a recipe – it’s a celebration of seasonal eating and a testament to the richness of Punjabi culture. Every bite carries the memory of grandmother’s kitchens, the warmth of the angeethi (hearth), and the joy of family gathered around a hearty meal. This winter, give yourself the pleasure of cooking this traditional dish slowly, and relish it with extra butter and love. As you scoop up the saag with pieces of makki di roti, you’ll understand why this simple greens curry has a legendary status. It’s homestyle Indian comfort food at its best – warm, earthy, and made with love. Happy cooking and Sat Sri Akal (salute to the truth)!